In a context of increasing use of data on market trends, consumer behaviour and studies on the purchasing journey, business management and operating decisions are more and more driven by scientific analysis. The old-style entrepreneur gut, which we might say still pays a big role in strategy in high complex situations, is taking a step back in front of mathematical minds. Certainly, the increasing role of online channels in the purchase, or in the adjacent phases of product search, assessment, and review, plays a decisive role in this shift.

However, in the overall dashboard of management decisions, the definition of a correct pricing still belongs, in most cases, to the more open area of art, with entrepreneurs asking advice to their crystal balls in defining the right strategy and values.

The purpose of this article, however, is not to show what are the right actions to follow in order to find the best correct pricing a company might apply, a sort of Holy Grail of the modern era, but how to abandon old habits inherited by dozens of years of management experience and behaviours inspired by a unique goal: “the maximization of it”.

This approach is not simply oriented to “customers”, but in general to “supply chain” actors. Managers do not only impose the highest prices a market might accept, but they put same effort and energy in negotiating discounted prices with own suppliers, with the overall purpose to take the “largest piece of the cake, whatever it takes”. Of course, not all managers and entrepreneurs have a strong proactive approach to it: some of them are employing all resources and techniques to obtain it, others simply act to enlarge the share as much as possible without making the attempt the reason of living. However, both sides are inspired by the same mentioned principle.

In recent years, thanks to an evolving movement that is creating pressure to adopt a more sustainable approach to business, more and more researchers published studies showing the great advantages in setting up the principle of “shared value” among the stakeholders and, in the specific field, the application of “fair pricing” within the overall concept of fairness toward customers and suppliers. The aim of this article is to inspire entrepreneurs to change their approach to this delicate management policy endorsing a new mindset and point of view, moving them from the “taking a pie share” versus the “sharing the pie”.

Entrepreneurs and managers have been taught by studies and business best practices to apply multiple techniques, first, in determining a pricing for their goods and services, and afterwards, in maximizing it. The art of “correct (maximized)” pricing is indeed almost in every industry matter for alchemists: am I pricing correctly for the market? Am I not losing value in my trade? How can I make higher profits, targeting a niche clientele with premium pricing or adopting a more competitive pricing but targeting mass markets[1]?

In academies and real case situations, events easing the process of maximizing revenues and margins (at least in the scope), are well known and clear: starting from manufacturing and operating costs (determining the price level to be surpassed to generate positive income), up to marketing (brand awareness…) and market factors (demand/supply balance, competitors presence and positioning…).

All these elements are ingredients that allow savvy managers to correctly take complex decisions on pricing and companies the aimed position in the market. What makes the work different in setting up the pricing with the purpose to make not just profits, but fair earnings, thus creating value for all stakeholders in the value chain? In other words, reaching an excellent market position where the margins are accrued for the wellbeing of the company internal (employees, shareholders, collaborators) and external (suppliers, customers, service providers) stakeholders? As for the best strategy in maximizing profits, there is not an optimal pre-established formula in maximizing this wider overall goal. But we can identify how to change approach in dealing with the most diffused decision-factors in price policies in order to achieve this shift toward trade agreements among players based on fairness, transparency and recognition of the contribution of each stakeholder. While this article focuses on B2B transactions, the same principle shall be applied in all value chain up to the end customer.

Withholding versus Sharing Value

To change the way companies set up their pricing, adopting a more “collective approach” to the matter, is indeed still a theoretical approach more than an operating roadmap, because it requires an alignment among supply chain players joining the negotiation process with a different mindset and scope. However, like all changes, pioneers need to start somewhere, and in some industries best practices have already started to be applied. Like in the overall ESG movement, where a real impact will be reached only through a collective adoption of sustainable practices, fair pricing (which is an ESG policy) requires shared values, reciprocal respect, and broader assessment of all stakeholders’ interests.

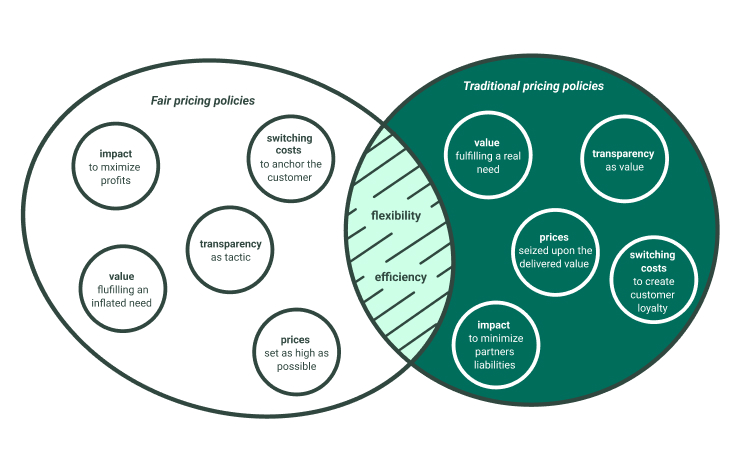

The following table lists some of the variables managers consider in setting up pricing, and while in some cases best management practices are already applied, in others the scope of fair principles requires a different approach.

Pricing strategies and elements: a comparable table

| FACTOR | TRADITIONAL PRICING | FAIR PRICING |

| Flexibility | Introducing components or options in the offer, making the overall proposal more flexible and adaptable to each single customer segment needs. By this clear management actions, the company invests in resources (product features and services) tailored to what, in reality, are the needs or the purchasing capability of various group of customers. We can classify these actions as “smart actions” that save resources and so let the company to lower prices according to the level of its proposal, and either traditional or fair approaches greatly benefit from them, because it allows not to add manufacturing or services costs which are not required by the customer (or that he can easily handle by himself). Example of actions within this category:Enabling wide product modularity (disaggregating features or accessories and letting the customer to configure the full package proposal adding product or service components upon choice)Providing transactional options, such as various payment terms (lease vs purchase, etc.)Engaging the customer in part of the work/process, in order to have her/him not to pay for it generating direct savings (for instance, through self-assembling or configuring the product) | |

| Value | The value the offer creates for the customer by fulfilling her/his needs and delivering a product or service that allows or ease a task, is or shall be always the centre of the marketing strategy and campaign. While it is so, companies are very well armed at adopt parallel marketing actions creating the need that in some case, like in lifestyle goods, is intangible or aspirational, so often not authentic. Marketers might argue that if a good fulfils wishes and dreams, it has always a positive effect and it delivers a promise for what the customer is willing to pay. And by these means, we do not necessarily condemn such strategies or actions, although in most of cases the value can be more “perceived” than “real”. By this factor, pricing is set upon the demand for it: the more the product is requested, the more the Company marks up its margins. | Value shall be clearly expressed by facts, explanation of the (authentic) benefits and the solution they provide for the customer. Listing the positive features, companies shall transparently admit the limitations of the same proposal, showing transparency, fair communication, and trustful message. This attitude pays back, reinforcing the trust, strengthening the company reputation, and establishing a direct and sincere connection with the audience.Whenever possible, the marketer shall highlight real benefits, even engaging psychologically the customer if this creates positive emotions and wellbeing in her/his purchase/adoption.The assessment of the real benefits provided by the offer compared to alternative solutions available in the market, shall be used to define the correct pricing. And in case the proposal enables savings (in terms of resources, like money, time or even easing its adoption), the company can even further markup the product while decreasing the costs of its audience, in a win-win scenario. |

| Impact | Practically, sellers shall understand the impact in the overall supplying costs of their customers. This will allow the seller to understand what capacity has in setting or raising the price upon the relevance of the item in the buyer purchasing budget. If the product costs a few dollars in a multi-million investment, the percentage of markup can be increased without being even detected by the buyer assessment. | Practically, sellers shall understand the impact in the overall supplying costs of their customers.If the product cost represents a great or tangible share, sellers must pay great attention in defining the boundaries of fair margins, with a purpose, going beyond the goal to achieve the sale, to respect the buyer needs and support his purchasing journey. However, in a fair trade, this applies to the contrary too: unleashing the fact price is not a relevant factor for the buyer gives room to obtain wider margin. The same can therefore be raised with a higher flexibility but within firm principles of the fair pricing. |

| Switching costs | The management doctrine lists clearly the context factors enabling a seller to determine “how much” he can increase the prices without losing the sale, or in general, maximizing profits (selling less but increasing the cumulated margins). This set of variables are named “switching cost” factors, and they include supply scarcity, product differentiation, available alternatives, brand loyalty, and time (limited time in the purchasing process gives buyer fewer options to choose). | Fair trade policies see switching costs differently. These factors shall be always maximized and nurtured by good management practices (creating a rigidity in the demand is always wise and an absolute goal to pursue), adopting however a different perspective. “Locking in” the customer shall be leveraged to create customer loyalty and retention, not as a factor to increase prices or negotiating power. The example provided by a context of supply scarcity is highlighting not even a monopoly shall obtain extra profits from this situation, but it shall keep a fair mindset, keeping margins at profitable level without taking the chance of an unbalanced bargaining power (a move that helps keeping as well potential newcomers attracted by otherwise high market margins). |

| Efficiency | Pursuing efficiency policies, limiting waste, fully exploiting existing assets, is a general management practice for all sort of companies, whatsoever ultimate strategy they pursue. Keeping levelled and monitored operating costs enables entrepreneurs to adopt competitive pricing, saving resources and maintaining as much flexible as possible its company. And for Fair companies, efficiency is altogether a source to create value for the community and the customers. | |

| Earnings | The company works to maximize its earnings, often reducing and optimizing costs, and trying to apply or negotiate the highest price accepted by “a sufficient number of customers” which allows an accrual of profits. On the first front (supplies), companies try to obtain “best sales terms” from their suppliers, and often, if their negotiating power is strong, to squeeze their margins. These practices have often the benefit to reduce company costs emerging in higher margins or more competitive pricing to end customers. But they might as well compromise supplier actions, capabilities to invest or to keep the quality of their product over the time.On the demand side, aggressive pricing and discounts and promotions are applied either because the product is not successful or correctly positioned, or to obtain a certain market share to defend it from competitors. | The company acts as “business and social player” with the mission to create value for all stakeholders, transforming products or delivering services to the customers, forming alliances with suppliers to maximize synergies and set up joint actions to improve their common supply chain, creating wellbeing to employees and the local communities and rewarding shareholders for their capital injections and risk.Such inclusive practices are possible if the company management adopts a wide angle in considering each stakeholder‘s point of view, needs and role. The company shall determine its market size and adopt a pricing allowing the accrual of fair earnings in comparison to the value that is created. Please note that this does not mean necessarily to determine pricing to earn decent but not high profits. Everything is in proportion of the generated value: if the company delivers tremendous value, it can accordingly raise prices, mighty ending up in generating a fortune. So, the focus is not in limiting price values as much as possible, but to withhold the supply chain value by its authentic contribution, keeping pricing/value ratio well balanced. |

| Transparency | Transparency is definitively limiting the room for autonomous management actions to maximize margins by edging differences in the market applying highest possible prices by channels, segments, and markets. This way, pricing is often disclosed only after extensive negotiations, sometime with the pretext of building a customized solution (not always different features provoke tangible different costs but is indeed a good pretext for a sales manager to settle it after detecting customer budget and expectations). | Transparency shall be a deliberate management option, and not necessarily solely a marketing move. Customers might greatly appreciate, and a clear pricing policy reinforces the building of a solid reputation for the company. At the same time sellers shall set it up with some caution because any variable pricing, while disclosed, shall be widely explained, and justified: the most advanced companies in this field have disclosed all cost and revenue components at the base of their price list. Ideally, to achieve the role of authentic players, companies shall altogether express prices “net”, for their ultimate value: in other words, they should not inflate them to create room for the negotiation, or to imitate industry standard whose default prices are given by a standard inflated value open to standard discounts“ |

The table has accomplished the task to show a set of variables the management shall consider to progressively shift from traditional to fair pricing policies. In doing so, companies need first to change behaviour in their trade, from negotiating to pursuing a joint value from the transaction; in other words, fair pricing is a part of wider fair management policies that shall be adopted by companies.

What to do? The recipe is simple, well presented above: applying flexibility, seeking efficiency, endorsing transparency, creating loyalty, and avoiding the temptation to leverage demand rigidity and segmenting market for the purpose of increasing margins upon the profile of the target.

It is not something happening overnight. Companies can start to work in each of the described areas of pricing policies to follow the guidelines improving consequently their practices. The shift might require an innovative mindset, changing the rules of the same industry they are in. How many times a company double its price list and applies 50% discount because “this is the standard”? Every competitor does so! Or again, I apply to you the 40% + 5% + 2% ??? What is this, a mathematical exercise? Companies shall always go out with a direct net price, and maybe being rigid in applying any negotiating discount just because the counterpart expects this (again, why he expects this? Because other players apply a markup to negotiate the same discount, not really a fair policy). Discount shall always be applicable, if possible, to quantities: this is a fair rule enabling different pricing by segment (consumer buys one unit for himself, distributor 100 to resell them…), and it is a consistent policy with the ultimate goal of fair earnings.

And if you lose values on the road, not maximizing profits in the transition period toward the new pricing policy, well, not necessarily it is a bad thing: you are building and communicating a culture of transparency and fairness to the market, and customers will definitively appreciate it, reinforcing your brand and competitive position and enabling, paradoxically, to adopt over the time (always “fair”) premium prices upon the earned market reputation.

A last note: such a transformation requires a collective adaptation, buyer-seller side, to a new business approach and negotiation culture. And a company can always face an “opportunistic” player trying to leverage “your fair pricing” into “maximize my profits” attitude! If educational efforts to change this approach do not work, your call: quit the deal, or fight back!

Borello Kingsley Antonio